Three Aspects of Art in Islam That Are Different That Western

Islamicate pointed arches and Byzantine mosaics complement each other inside the Palatine Chapel, Sicily.

The Romanesque portal at Moissac—see text. Detail of the tympanum here

Islamic influences on Western art refers to the stylistic and formal influence of Islamic art, divers every bit the artistic production of the territories ruled by Muslims from the 7th century onward, on European Christian art. Western European Christians interacted with Muslims in Europe, Africa, and the Middle E and formed a relationship based on shares ideas artistic methods.[i] Islamic art includes a wide variety of media including calligraphy, illustrated manuscripts, textiles, ceramics, metalwork, and glass, and because the Islamic world encompassed people of various religious backgrounds, arstists and craftsman were not always Muslim, and came from a broad diversity of different backgrounds. Glass production, for instance, remained a Jewish speciality throughout the menstruum. Christian fine art in Islamic lands, such as that produced in Coptic Egypt or by Armenian communities in Islamic republic of iran, continued to develop under Islamic rulers.

Islamic decorative arts were highly valued imports to Europe throughout the Middle Ages. In the early catamenia, textiles were particularly important, due to the labor intensive nature of their product. These textiles originating in the Islamic globe were frequently used for church building vestments, shrouds, hangings and clothing for the elite. Islamic pottery of everyday quality was withal preferred to European wares.[ii]

In the early centuries of Islam, the almost of import points of contact betwixt the Latin W and the Islamic earth from an creative signal of view were Southern Italy, Sicily, and the Iberian peninsula, which both held pregnant Muslim populations. After the Italian maritime republics were important in trading artworks. In the Crusades, Islamic art seems to have had relatively niggling influence fifty-fifty on the Crusader art of the Crusader kingdoms, though information technology may accept stimulated the want for Islamic imports among Crusaders returning to Europe. Islamic architecture, even so, appeared to influence the designs of Templar churches inside the Middle East and other cathedrals within Europe upon the return of Crusaders in the twelfth and 13th century.[3]

Numerous techniques from Islamic art formed the footing of art in the Norman-Arab-Byzantine civilization of Norman Sicily, much of which used Muslim artists and craftsmen working in the fashion of their own tradition. Techniques included inlays in mosaics or metals, often used for architectural decoration, porphyry or ivory carving to create sculptures or containers, and statuary foundries.[four] In Iberia the Mozarabic fine art and architecture of the Christian population living under Muslim rule remained very Christian in most ways, but showed Islamic influences in other respects; much what was described every bit this is now chosen Repoblación fine art and architecture. During the late centuries of the Reconquista Christian craftsmen started using Islamic artistic elements in their buildings, as a result the Mudéjar mode was developed.

Heart Ages [edit]

Map showing the primary trade routes of late medieval Europe.

Islamic art was widely imported and admired past European elites during the Middle Ages.[v] At that place was an early on formative stage from 600-900 and the evolution of regional styles from 900 onwards. Early Islamic art used mosaic artists and sculptors trained in the Byzantine and Coptic traditions.[6] Instead of wall-paintings, Islamic fine art used painted tiles, from as early as 862-iii (at the Great Mosque of Kairouan in modernistic Tunisia), which as well spread to Europe.[7] According to John Ruskin, the Doge'due south Palace in Venice contains "three elements in exactly equal proportions — the Roman, the Lombard, and Arab. It is the central edifice of the globe. ... the history of Gothic architecture is the history of the refinement and spiritualization of Northern work under its influence".[viii]

Throughout the Middle Ages, Islamic rulers controlled at various points parts of Southern Italy, the island of Sicily, and most of modernistic Espana and Portugal, as well as the Balkans, all of which retained large Christian populations. The Christian Crusaders also held territory in regions of the Islamic globe, and ruled over some Muslim populations. Crusader art is mainly a hybrid of Catholic and Byzantine styles, showing little Islamic influence; however, the Mozarabic art of Christians in Al Andalus seems to testify considerable influence from Islamic art. Islamic influence can besides exist traced in Romanesque and Gothic fine art in northern European art. For example, in the Romanesque portal at Moissac in southern France, the scalloped edges to the doorway and the circular decorations on the lintel in a higher place, take parallels in Iberian Islamic fine art. The depiction of Christ in Majesty surrounded by musicians, which was to become a common feature of Western heavenly scenes, may derive from courtly images of Islamic rulers.[11] Calligraphy, ornament, and the decorative arts generally were more important than in the West.[12]

The Hispano-Moresque pottery wares of Spain were start produced in Al-Andalus, but Muslim potters then seem to have emigrated to the area of Christian Valencia. Hither they produced piece of work that was exported to Christian elites across Europe;[13] other types of Islamic luxury goods, notably silk textiles and carpets, came from the mostly wealthier[14] eastern Islamic world itself (the Islamic conduits to Europe w of the Nile were, however, not wealthier),[fifteen] with many passing through Venice.[xvi] Nevertheless, for the about part luxury products of the court culture such as silks, ivory, precious stones and jewels were imported to Europe simply in an unfinished form and manufactured into the terminate production labelled every bit "eastern" by local medieval artisans.[17] They were complimentary from depictions of religious scenes and usually busy with ornament, which fabricated them like shooting fish in a barrel to accept in the West,[18] indeed by the belatedly Centre Ages there was a way for pseudo-Kufic imitations of Arabic script used decoratively in Western fine art.

Decorative arts [edit]

Hispano-Moresque dish, approx 32cm diameter, with Christian monogram "IHS", busy in cobalt blue and gold lustre, Valencia, c.1430-1500.

Until the end of the Middle Ages, many European produced goods could not match the quality of objects originating from areas in the Islamic globe or the Byzantine Empire. Because of this, a wide variety of portable objects from various decorative arts were imported from the Islamic world into Europe during the Middle Ages, mostly through Italy, and above all Venice.[19] Venetians visited cities like Damascus, Cairo, and Aleppo throughout the Eye Ages. When they would visit these Muslim centers, they would bring back new ideas for art and architecture. The city of Venice was congenital with a Christian population in mind, but implemented many archetype Islamic elements, and the merchant-city reputation of Venice helped solidify the blend of Islamic and Christian cultures at the time.[20] In many areas European-fabricated appurtenances could not match the quality of Islamic or Byzantine work until virtually the end of the Middle Ages. Luxury textiles were widely used for clothing and hangings and besides, fortunately for art history, as well often every bit shrouds for the burials of important figures, which is how most surviving examples were preserved. In this area Byzantine silk was influenced by Sassanian textiles, and Islamic silk past both, then that is hard to say which civilisation's textiles had the greatest influence on the Cloth of St Gereon, a big tapestry which is the earliest and virtually important European false of Eastern work. European, especially Italian, cloth gradually caught up with the quality of Eastern imports, and adopted many elements of their designs.

Byzantine pottery was not produced in loftier-quality types, as the Byzantine elite used silver instead. Islam has many hadithic injunctions against eating off precious metal, and so developed many varieties of fine pottery for the elite, often influenced past the Chinese porcelain wares which had the highest condition among the Islamic elites themselves — the Islamic only produced porcelain in the modernistic period. Much Islamic pottery was imported into Europe, dishes ("bacini") fifty-fifty in Islamic Al-Andalus in the 13th century, in Granada and Málaga, where much of the production was already exported to Christian countries. Many of the potters migrated to the surface area of Valencia, long reconquered by the Christians, and product here outstripped that of Al-Andalus. Styles of ornament gradually became more than influenced by Europe, and by the 15th century the Italians were likewise producing lustrewares, sometimes using Islamic shapes like the albarello.[21] Metalwork forms like the zoomorphic jugs called aquamanile and the bronze mortar were besides introduced from the Islamic world.[22]

Mudéjar art in Spain [edit]

Mudéjar fine art is a style influenced by Islamic fine art that developed from the twelfth century until the 16th century in the Iberia's Christian kingdoms. Information technology is the outcome of the convivencia between the Muslim, Christian and Jewish populations in medieval Spain. The elaborate ornament typical of Mudéjar way fed into the development of the later Plateresque style in Spanish architecture, combining with late Gothic and Early Renaissance elements.

Pseudo-Kufic [edit]

Chief Alpais' ciborium, circa 1200 with rim engraved with Arabic script, Limoges, French republic, 1215-thirty. Louvre Museum MRR 98.

The Arabic Kufic script was often imitated in the West during the Middle-Ages and the Renaissance, to produce what is known as pseudo-Kufic: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is nigh usually used in Islamic architectural decoration".[23] Numerous cases of pseudo-Kufic are known in European religious fine art from around the tenth to the 15th century. Pseudo-Kufic would be used as writing or as decorative elements in textiles, religious halos or frames. Many are visible in the paintings of Giotto.[23]

Examples are known of the incorporation of Kufic script such equally a 13th French Principal Alpais' ciborium at the Louvre Museum.[N ane] [24]

Compages [edit]

Arab-Norman culture in Sicily [edit]

An example of this blended art style can exist seen in the Mantle of Roger Two. Designed in Norman Sicily, it went on to be the coronation garb for the Holy Roman Empire. The mantle depicts lions overcoming camels, symbolic imagery to allude to the Norman conquering of Arab territory. This symbol also draws from Islamic cultures' usage of the king of beasts as a symbol of victory at the time, though information technology flips the context, as it is being used to draw the Norman victory over the Arabs.[25] The inscription on the mantle is besides written in Standard arabic, referencing the culture and linguistic communication of the lands they overthrew.

The Normans of Sicily were located at a crossroads betwixt European Chistian cultures, and the islamic worlds of Spain, North Africa, Western Asia. Though they were a Christian culture, the lands they ruled over had been previously occupied by Arab Islamic rule until the Normans overtook it in 1060,[25] and their art style reflects this previous Arab leadership and existence at a middle ground in the Medieval world.[25]

Christian buildings such as the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, Sicily, incorporated Islamic elements, probably usually created past local Muslim craftsmen working in their own traditions. The ceiling at the Cappella, with its wooden vault arches and gilded figurines, has close parallels with Islamic buildings in Fez and Fustat, and reflect the Muqarnas (stalactite) technique of emphasizing three-dimensional elements[26]

The diaphragm arch, Late Antiquarian in origin, was widely used in Islamic architecture, and may have spread from Spain to France.[27]

Islamic Influence on Gothic Architecture [edit]

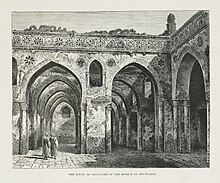

The Liwan or Sanctuary of the Mosque of Ibn-Tuloon (1878)[N ii]

Western scholars of the 18–19th century, who mostly preferred Classical art characterized Gothic art as "disorder[ed]", causing several to draw similarities between Gothic and Islamic architecture. The theory that the Gothic architectural style was influenced by Islamic architecture was made widely known by Sir Christopher Wren in his Parentalia (1750). Wren argued that the pointed arch and ribbed-vaulting characteristics of the Gothic style were borrowed from the Saracens, a derogatory term referring to Muslims, typically Arab Muslims, therefore Gothic art should be called the "Saracen way" of architecture.[28] William Hamilton commented on the Seljuks monuments in Konya: "The more than I saw of this peculiar style, the more I became convinced that the Gothic was derived from it, with a certain mixture of Byzantine (...) the origin of this Gotho-Saracenic style may be traced to the manners and habits of the Saracens"[N 3] [29]

The eighth century Umayyad Caliphate within the Iberian peninsula was credited with introducing many elements adopted into Gothic compages within Spain, and Christian Crusaders returning home to Europe in the twelfth and 13th century carried Islamic architectural influences with them into France and later England.[iii] Several attributes of Gothic architecture take been attributed to being borrowed from Islamic styles. The 18th-century English historian Thomas Warton summarized:

"The marks which constitute the character of Gothic or Saracenical compages, are, its numerous and prominent buttresses, its lofty spires and pinnacles, its large and ramified windows, its ornamental niches or canopies, its sculptured saints, the delicate lace-work of its fretted roofs, and the profusion of ornaments lavished indiscriminately over the whole building: simply its peculiar distinguishing characteristics are, the minor cluttered pillars and pointed arches, formed by the segments of two interfering circles"

When Sir. Christopher Wren constructed St. Paul'due south Cathedral in London, he admitted the use of "Saracen vaulting," referring to the ribbed-vaulting typical of Islamic mosques, such every bit in the Great Mosque of Cordoba.[3]

Wren'due south attribution of the Gothic's way's pointed arch to Islamic architecture was corroborated by 21st century scholar Diana Darke, who in Stealing from the Saracens: How Islamic Compages Shaped Europe explains that the pointed arch outset appeared in the 7th century Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which was congenital past the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik.[3] Furthemore, the trefoil curvation, which was adopted by Gothic architects to symbolize the Holy Trinity, first appeared within Umayyad shrines and palaces before it was seen in European architecture.[3] Darke's statement that Western Gothic art was borrowed direct from Islamic art has been criticized for ignoring cross-cultural influences in Islamic art itself, which brand information technology difficult to make up one's mind which architectural elements were created by whom in a strictly linear evaluation.[3]

Pointed arch [edit]

The pointed arch originated in the Byzantine and Sassanian empires, where it more often than not appears in early churches in Syria. The Byzantine Karamagara Bridge has curved elliptical arches rising to a pointed keystone.[xxx] The priority of the Byzantines in its utilise is likewise evidenced by slightly pointed examples in Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, and the Hagia Irene, Constantinople.[30] The pointed curvation was subsequently adopted and widely used by Muslim architects, becoming the characteristic arch of Islamic architecture.[xxx] According to Bony, information technology has spread from Islamic lands, peradventure through Sicily, and then under Islamic rule, and from there to Amalfi in Italy, before the end of the 11th century.[31] [32] The pointed curvation reduced architectural thrust past about twenty% and therefore had practical advantages over the semi-round Romanesque arch for the building of big structures.[31]

The pointed arch as a defining characteristic of Gothic compages appears to take been introduced from the Islamic, in some areas, but to have evolved as a structural solution in late Romanesque, both in England at Durham Cathedral and in the Burgundian Romanesque and Cistercian architecture of France.[33]

Templar churches [edit]

Seal of the Knights Templar featuring a domed building, whether from a dome from Al-Aqsa, the Dome of the Rock or the aedicula of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

In 1119, the Knights Templar received as headquarters part of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, considered by the crusaders the Temple of Solomon, from which the club took its common name. Around a decade later, the purple palace moved their headquarters to near the Temple of David, and the Knights Templar took over all of the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Subsequently, the Templar order built secular and religious structures within the mosque's area, like multiple cloisters, shrines, and a church. It's likely that the Templars used the Dome of the Rock, also known as al-Haram al-Sharif, as a standard to reach in terms of architectural beauty.[34] The typical round churches built by the knights across Western Europe, such as the London Temple Church, are probably inspired past the shape of Al-Aqsa or the Dome of the Rock (known to Muslims as al-Haram al-Sharif)[35]

Islamic elements in Renaissance art [edit]

Pseudo-Kufic [edit]

Pseudo-Kufic is a decorative motif that resembles Kufic script and occurs in many Italian Renaissance paintings. The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic in early Renaissance works is unclear. Information technology seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13th–14th-century Centre-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus's fourth dimension, and thus plant natural to correspond early Christians in association with them:[37] "In Renaissance art, pseudo-Kufic script was used to decorate the costumes of Old Testament heroes similar David".[38] Mack states another hypothesis:

Peradventure they marked the imagery of a universal faith, an creative intention consistent with the Church building's contemporary international program.[39]

Heart Eastern Carpets [edit]

Verrocchio's Madonna with Saint John the Baptist and Donatus 1475-1483 with small-blueprint Holbein Islamic carpet at her feet.

Carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from the Ottoman Empire, the Levant or the Mamluk country of Egypt or Northern Africa, were used as important decorative features in paintings from the 13th century onwards, and peculiarly in religious painting, starting from the Medieval menses and standing into the Renaissance period.[40]

Such carpets were ofttimes integrated into Christian imagery as symbols of luxury and status of Middle-Eastern origin, and together with Pseudo-Kufic script offering an interesting example of the integration of Eastern elements into European painting.[forty]

Anatolian rugs were used in Transylvania every bit decoration in Evangelical churches.[41]

Islamic costumes [edit]

Islamic individuals and costumes often provided the contextual backdrop to depict an evangelical scene. This was particularly visible in a ready of Venetian paintings in which contemporary Syrian, Palestinian, Egyptian and specially Mamluk personages are employed anachronistically in paintings describing Biblical situations.[42] An example in point is the 15th century The Arrest of St. Mark from the Synagogue by Giovanni di Niccolò Mansueti which accurately describes contemporary (15th century) Alexandrian Mamluks arresting Saint Mark in an historic scene of the 1st century CE.[42] Some other case is Gentile Bellini'south Saint Marker Preaching in Alexandria.[43]

Ornament [edit]

A Western style of ornament based on the Islamic arabesque developed, beginning in late 15th century Venice; it has been called either moresque or western arabesque (a term with a complicated history). It has been used in a slap-up diverseness of the decorative arts but has been especially long-lived in volume pattern and bookbinding, where pocket-size motifs in this manner take continued to exist used by bourgeois book designers up to the present mean solar day. It is seen in gold tooling on covers, borders for illustrations, and printer's ornaments for decorating empty spaces on the page. In this field the technique of gold tooling had also arrived in the 15th century from the Islamic world, and indeed much of the leather itself was imported from at that place.[44]

Like other Renaissance ornament styles it was disseminated by ornament prints which were bought as patterns by craftsmen in a variety of trades. Peter Furhring, a leading specialist in the history of ornament, says that:

The ornamentation known as moresque in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (merely now more usually called arabesque) is characterized by bifurcated scrolls composed of branches forming interlaced leafage patterns. These basic motifs gave rise to numerous variants, for example, where the branches, generally of a linear graphic symbol, were turned into straps or bands. ... It is feature of the moresque, which is essentially a surface ornament, that it is incommunicable to locate the pattern's starting time or end. ... Originating in the Eye Due east, they were introduced to continental Europe via Italy and Spain ... Italian examples of this ornament, which was oftentimes used for bookbindings and embroidery, are known from every bit early as the late fifteenth century.[45]

Elaborate book bindings with Islamic designs can be seen in religious paintings.[46] In Andrea Mantegna'south Saint John the Baptist and Zeno, Saint John and Zeno concur exquisite books with covers displaying Mamluk-manner center-pieces, of a blazon also used in contemporary Italian book-binding.[47]

Influence in North America [edit]

Moorish architecture appeared in the Americas as early every bit the inflow of the Spanish led by Christopher Columbus in 1492. Many of the settlers from Kingdom of spain were craftsmen and builders that converted to Christianity from Islam, bringing "domes, eight-pointed stars, quatrefoil elements, ironwork, courtyard fountains, balconies, towers, and colorful tiles" as noted past historian Phil Pasquini.[48] The oldest building in the United states of america that was influenced by Islamic compages is the Alamo. Ane of five missions in the area, it was supposed to include a dome and tower every bit per Moorish design, just was left in ruins after the boxing of the Alamo in 1836.[48]

21st Century [edit]

After the attacks of September 11, 2001, Islamic art and architecture has seen a decline in popularity in the U.s.a.. There are a few popular Islamic influenced tourist attractions in the United states of america, such as the Morocco pavilion in Disney'due south Epcot, the Irvine Spectrum Center in Irvine, California, and the Islamic-themed city of Opa-Locka, Florida.[48]

Encounter also [edit]

- Islamic influence on medieval Europe

Notes and references [edit]

Explanatory notes and item notices [edit]

- ^ Muriel Barbier. "Principal Alpais' ciborium – Master Yard. ALPAIS – Decorative Arts". Louvre museum website. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15.

- ^ Ebers, Georg. "Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque." Book i. Cassell & Company, Limited: New York, 1878. p 213

- ^ William J. Hamilton (1842) Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia p.206

- ^ Thomas Warton (1802), Essays on Gothic architecture p.14

Notes [edit]

- ^ Heschel, Susannah; Ryad, Umar (2019). The Muslim Reception of European Orientalism. New York: Routledge. ISBN978-1-138-23203-7.

- ^ Mack 2001, pp. 3–viii, and throughout

- ^ a b c d e f VerfasserIn., Darke, Diana (2020). Stealing from the Saracens how Islamic architecture shaped Europe. ISBN978-1-78738-305-0. OCLC 1197079954.

- ^ Aubé 2006, pp. 164–165

- ^ Hoffman, 324; Mack, Chapter 1, and passim throughout; The Art of the Umayyad Period in Spain (711–1031), Metropolitan Museum of Art timeline Retrieved April 1, 2011

- ^ Honor & Fleming 1982, pp. 256–262.

- ^ Accolade & Fleming 1982, p. 269.

- ^ The Stones of Venice, chapter 1, paras 25 and 29; discussed pp. 49–56 hither [i]

- ^ "CNG: Feature Auction CNG 70. Spain, Castile. Alfonso VIII. 1158-1214. AV Maravedi Alfonsi-Dobla (3.86 grand, 4h). Toledo (Tulaitula) mint. Dated Safar era 1229 (1191 Advert)". world wide web.cngcoins.com . Retrieved 2020-05-30 .

- ^ "Coin - Portugal". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2020-05-30 .

- ^ Beckwith 1964, pp. 206–209.

- ^ Jones, Dalu & Michell, George, (eds); The Arts of Islam, Arts Council of Great Britain, 9, 1976, ISBN 0-7287-0081-6

- ^ Caiger-Smith, chapters 6 & 7

- ^ Hugh Thomas, An Unfinished History of the Earth, 224-226, 2nd edn. 1981, Pan Books, ISBN 0-330-26458-3; Braudel, Fernand, Civilisation & Capitalism, 15-18th Centuries, Vol i: The Structures of Everyday Life, William Collins & Sons, London 1981, p. 440: "If medieval Islam towered over the Sometime Continent, from the Atlantic to the Pacific for centuries on end, it was because no state (Byzantium apart) could compete with its gilt and silvery money ..."; and Vol 3: The Perspective of the World, 1984, ISBN 0-00-216133-8, p. 106: "For them [the Italian maritime republics], success meant making contact with the rich regions of the Mediterranean - and obtaining gilded currencies, the dinars of Arab republic of egypt or Syrian arab republic, ... In other words, Italy was still simply a poor peripheral region ..." [period before the Crusades]. The Statistics on Earth Population, GDP and Per Capita Gross domestic product, 1-2008 Advertising compiled by Angus Maddison show Iran and Iraq as having the earth'southward highest per capita GDP in the year 1000

- ^ Rather than forth religious lines, the divide was between east and due west, with the rich countries all lying east of the Nile: Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the Globe Economic system, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economical History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-nineteen-922721-one, p. 382, table A.7. and Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the World Economic system, one–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economical History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 185, table iv.ii requite 425 1990 International Dollars for Christian Western Europe, 430 for Islamic N Africa, 450 for Islamic Spain and 425 for Islamic Portugal, while only Islamic Arab republic of egypt and the Christian Byzantine Empire had significantly higher Gross domestic product per capita than Western Europe (550 and 680–770 respectively) (Milanovic, Branko (2006): "An Estimate of Average Income and Inequality in Byzantium around Year 1000", Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 449–470 (468))

- ^ The subject of Mack's volume; the Introduction gives an overview

- ^ Hoffman, Eva R. (2007): Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century, pp.324f., in: Hoffman, Eva R. (ed.): Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-five

- ^ Mack, 4

- ^ The subject of Mack'due south book; run across Chapter one specially.

- ^ Howard, Deborah (2000). Venice and the East. Connecticut: Yale. ISBN0-300-08504-4.

- ^ Caiger-Smith, Capacity 6 and 7

- ^ Jones & Michell 1976, p. 167

- ^ a b Mack 2001, p. 51

- ^ La Niece, McLeod & Rohrs 2010

- ^ a b c R., Hoffman, Eva (2007). Pathways of portability : Islamic and christian interchange from the tenth to the twelfth century. OCLC 886982374.

- ^ Kleinhenz & Barker 2004, p. 835

- ^ Bony 1985, p. 306

- ^ Tonia., Raquejo (1986). The "arab cathedrals" : moorish architecture as seen by British travellers. Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd. OCLC 1026541162.

- ^ Schiffer 1999, p. 141 [ii]

- ^ a b c Warren, John (1991), "Creswell's Use of the Theory of Dating by the Acuteness of the Pointed Arches in Early Muslim Architecture", Muqarnas, vol. eight, pp. 59–65

- ^ a b Bony 1985, p. 17

- ^ Kleiner 2008, p. 342

- ^ Bony 1985, p. 12

- ^ Chase, Lucy-Anne (July 2000). "Crusader Sculpture and the So-Called 'Templar Workshop': A Reassessment of 2 Carved Panels from the Dome of the Stone in the Haram Al-Sharif Museum in Jerusalem". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 132 (2): 131–156. doi:ten.1179/peq.2000.132.two.131. ISSN 0031-0328. S2CID 161235781.

- ^ God and Enchantment of Place: Reclaiming Human Experience, David Brown, Oxford Academy Press, 2004, page 203.

- ^ Mack 2001, pp. 65–66

- ^ Mack 2001, pp. 52, 69

- ^ Freider. p.84

- ^ Mack 2001, p. 69

- ^ a b Mack 2001, pp. 73–93

- ^ Ionescu, Stefano (2005). Antiquarian Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania (PDF) (1st ed.). Rome: Verduci Editore. Retrieved 29 Oct 2016.

- ^ a b Mack 2001, p. 161

- ^ Mack 2001, pp. 164–65

- ^ Harthan 1961, pp. 10–12

- ^ Fuhring 1994, p. 162

- ^ Mack 2001, pp. 125–37

- ^ Mack 2001, pp. 127–28

- ^ a b c Pasquini, Phil (2012). Domes, Arches, and Minarets: a history of Islamic-inspired buildings in America. Flypaper. ISBN978-0-9670016-1-6.

References [edit]

- Aubé, Pierre (2006). Les empires normands d'Orient (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN2-262-02297-6.

- Beckwith, John (1964), Early on Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque , Thames & Hudson, ISBN0-500-20019-X

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Compages of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. California studies in the history of art. University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-05586-5.

- Fuhring, Peter (1994). "Renaissance Decoration Prints; The French Contribution". In Jacobson, Karen (ed.). The French Renaissance in prints from the Bibliothèque Nationale de French republic. (oft wrongly cat. equally George Baselitz). Grunwald Center, UCLA. ISBN0-9628162-2-ane.

- Grabar, Oleg (2006). Islamic visual culture, 1100 - 1800. Constructing the report of Islamic art. Vol. 2. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN978-0-86078-922-two.

- Harthan, John P. (1961). Bookbinding (2nd rev. ed.). HMSO (for the Victoria and Albert Museum). OCLC 220550025.

- Hoffman, Eva R. (2007): Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the 12th Century, in: Hoffman, Eva R. (ed.): Late Antiquarian and Medieval Fine art of the Mediterranean Globe, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-v

- Award, Hugh; Fleming, John (1982), "Honour", A World History of Fine art, London: Macmillan

- Jones, Dalu; Michell, George, eds. (1976). The Arts of Islam. Arts Council of Great Uk. ISBN0-7287-0081-six.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2008). Gardner's fine art through the ages: the western perspective (thirteen, revised ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN978-0-495-57355-5.

- Kleinhenz, Christopher; Barker, John W (2004). Medieval Italian republic : an encyclopedia, Volume 2. Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-93931-7.

- La Niece, Susan; McLeod, Bet; Rohrs, Stefan (2010). The Heritage of "Maitre Alpais": An International and Interdisciplinary Exam of Medieval Limoges Enamel and Associated Objects. British Museum Research Publication. ISBN978-0-86159-182-4.

- Mack, Rosamond Eastward. (2001). Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Merchandise and Italian Art, 1300-1600. Academy of California Printing. ISBN0-520-22131-1.

- Schiffer, Reinhold (1999). Oriental panorama: British travellers in 19th century Turkey. Rodopi. ISBN978-90-420-0407-8.

Further reading [edit]

- Caiger-Smith, Alan (1985). Lustre Pottery: Technique, Tradition and Innovation in Islam and the Western World. Faber and Faber. ISBN0-571-13507-2.

- Watkin, David (2005). A history of Western architecture (four ed.). Laurence King Publishing. ISBN978-1-85669-459-9.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_influences_on_Western_art

0 Response to "Three Aspects of Art in Islam That Are Different That Western"

Post a Comment